Stories Deployed

Vol. 1, Issue 1

The Veteran Chronicles

Acknowledgments

The English Department at Western Washington University has supported Stories Deployed: The Veteran Chronicles since it began as a reading series in 2012, and this year in print form. We are deeply grateful for this ongoing support. This project was also funded by the Dean’s Fund for Excellence in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Thanks to Dean Paqui Paredes Mendez for understanding how much this means to Western veterans, alumni veterans, and veterans in the larger community. We are also grateful to the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs for deeming this project worthy of a grant. We’d also like to thank the WWU Veterans Services Office, because everyone there has always been willing to pitch in and lend a hand. Lastly, thanks to the Red Badge Project of Seattle for sponsoring many of the workshops in which this writing was produced.

Stories Deployed, Wilson Library, May 2018. Mark Okinaka performing.

Introduction

by Kathryn Trueblood, writer and professor of English at Western Washington University

Pictured left to right: Russ Thompson, Liz Harmon Craig, Gordon Rodgers, Keith Fletcher, Kate Trueblood, Dominick Cordero, Mark Okinaka, Michael Woelkers, Jerry Wade.

Jesse Atkins aptly named this storytelling performance by veterans. When we met, we were two people with similar feelings about the disconnect between Main Street and the military. Because my father was a captain in the Army, I understood what was happening in my classrooms after 9/11 when my students who were National Guard or Military Reservists disappeared, while many in their cohort didn’t seem to be aware of what was going on. As a teacher of writing, I was attending conferences where I learned about a movement among writers to share storytelling techniques with veterans so that they could give voice to their experiences. Operation Homecoming was the first and largest, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, but then came The Veterans Writing Project, Warrior Writers, and the Red Badge Project. So I went to find Jesse Atkins, who was then the Veterans Outreach Coordinator, and I learned that he had a love of writing that had started when he was a submariner, or “bubblehead,” as he would say. We decided to hold free writing workshops in the late afternoon on campus to see if we could get a group going. Only one person came: the enthusiastic Tsonsera Rhoades, God bless her. Jesse was undeterred, optimistic even. I asked him, “Where do campus veterans hang out?”

He told me, “Folks like to gather at the VFW on Friday nights to eat pizza and drink beer.”

“So, let’s go there,” I said. He agreed and we made up flyers. I also reached out to the writing group at the Bellingham Veterans Center, and they came down to share some of their work. Most of them were Vietnam Vets, and they wrote stories that could curl your hair, stories that emboldened the younger people who were mostly veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. There were some intense exchanges, and I learned not to get in the way when tough things needed to surface. I also learned I could trust vets to show up for each other powerfully, unfailingly. And that nobody has a darker sense of humor than a vet. Eventually, we moved to Saturday workshops, and I actually got some formal training from the Red Badge Project, though the vets themselves were my best teachers and never seemed to mind when I was flying by the seat of my pants.

Mostly, I am humbled by the quality of the writing they produced over the eight years we did this. The essays, poems, and stories in this book defy expectation. When you read this collection, you will learn what it’s like to volunteer in an Iraqi hospital after a bombing; what it’s like to guard the border between Egypt and Israel as part of a multi-national peacekeeping force; what’s it like to be a gay female soldier in a strip club in the Philippines; what it’s like to lose more of your company stateside than in Afghanistan; what’s it like to survive a firefight, be it in Vietnam or Afghanistan; and what’s it like to come home and attend college after combat. Many veterans will tell you that returning is the hardest part. Native American cultures understand the importance of ceremony as a way of helping the warrior to return. In some cultures, the soldier isn’t considered truly home until the community has heard his or her stories. Stories Deployed: The Veteran Chronicles was founded to recognize this need. Given that only 1% of the population makes up our volunteer army, most of us don’t know what we mean when we say, “Thank you for your service.” We are just not aware of what that might entail. And that’s a shame. I hope your respect is deepened by reading the stories herein. It has been an honor to publish them.

The Gettysburg Address: A Walk in the Park

by Stephen Allison

She had red hair, long red hair with the smallest of curls at the ends. And she had this feather, like from a peacock or something, and she was moving it ever so lightly across my forehead and around and down my neck. She’d follow a path down around to my lower back and work her way toward my feet, go in between my toes and swirl this feather back up my legs. She knew exactly what she was doing. God, please let this last all night!

One knows long before sunrise what kind of day it’s going to be in the desert of northern Africa. The Sinai mornings come slow and deliberate like a string of camels creeping over the mountains through the fog a hundred miles away. Like a flunky doing mail call for those unknown to him, morning is indifferent. Laden with parcels that can make or break someone’s day, it is passionate only about its mission of heralding the new day. With each morning come these parcels that contain both the predicted and the unexpected.

There are the biting flies that come relentlessly in search of moisture in order to sustain their life. Mercilessly, they target the inside of the nostrils, wriggling and absorbing as they go. They seek soaked armpits, sweatbands, and dozens will cover a canteen when even a few drops of water are spilled. Best described as ruthless are the tactics employed by these black, buzzing, and biting monsters. They heed no clock, ignore all weather, and are ever present. They are skilled searchers and rarely give up until moisture is found. And there is the second largest arachnid on the continent, the camel spider, who, while the victim sleeps, will nibble and gnaw unobtrusively and create a necrotic hole bigger than a half-dollar in minutes. Wandering bands of nomadic Bedouins, while native to this land for thousands of years, still fall prey to these silent, agile, hairy beasts who weigh as much as an ounce. And so will all who fail to obey the first law of this land: Keep Your Head on a Swivel, Stay alert, Stay Alive.

Some would ask which is more draining on a person whose goal is to stay alert and alive in this the harshest of environments on earth: the physical, emotional, or psychological aspects of survival? Which, if any, has precedence? There is no correct answer unless one responds with “It depends.” One’s head must be on that swivel and one must be constantly aware. Biting flies and spiders the size of a baseball are one thing, but there are other issues with which to contend.

There are pitfalls that are even worse waiting for the uninitiated or careless who don’t realize their lives hang by a hair. The desert environment, while truly indifferent, is capable of being kind as well as wicked. It can sustain and nourish certain lives while it disables and exterminates others. It possesses no conscious desire to acquiesce, to give in, or to favor. Then there are man-made dangers as well, and unlike creatures that inhabit the desert these dangers are unpredictable.

Stephen Allison in Egypt 1988

“MOFO”, “Wally World”, and “The World’s Biggest Ashtray” are a few of the pet names given to a particular geographic location in the northern Sinai. It is, in area, one mile by one mile and home to small components of military personnel from eleven different nations. The firebase is bounded by a perimeter of steel reinforced fencing, has manned guard towers with 50-caliber machine guns every 300 yards, and there is only one way in or out. The primary mission of soldiers at Wally World is to patrol and maintain security of the border between Egypt and Israel. Each national contingent has a unique mission, whether it be within the walls or out, that supports the primary mission. There are French pilots, British administrators, and Canadian and Dutch communication specialists and military police. The job of the infantry falls to Colombia, the United States, Fiji, New Zealand, and Australia. Uruguay and Norway provide sailors to sweep the Red Sea of ancient and not so ancient mines. The true name of this elite force is the Multi-National Peace-Keeping Force and Observers, called MFO for short, and the proper name for its location is El Gorah, Sinai, Egypt.

From June 1988 until June 1989 I was assigned to the MFO. The idea that one can take time to learn about the predictable and unexpected in this barren tan wasteland remains questionable at best. On July 17, 1988 after being on the ground for only a month and a half, I was chosen by fate to participate in a life-changing experience along with four other soldiers that made biting flies and spiders pale by comparison.

Our five-man patrol had been in operation for some seven days. We were 75 kilometers from any support and were on a well established patrol route that allowed reconnaissance to either side of the border. As senior man I had the responsibility of making sure everyone was up and ready to move at the first hint of daylight, so I was usually awake before anyone else. I clearly remember on this particular morning fighting with the creeping heat, arguing and losing the fight about waking, and how disappointed I was when I realized that the girl with the feather was not a girl with a feather. Shit!

It had been a dream. The feather turned out to be sweat. I should have known. As the sweat pooled in my eye sockets, it created miniature lakes for biting flies to swim in. It ran down the middle of my back and it dripped off my ear lobes, and when I finally realized that she and her feather were gone I started feeling sorry for myself. Then I had to laugh. I should have known. I wanted to spend more time with this woman with red hair who seemed so real. But our morning had come, and there was business to take care of. I remember thinking, hoping, that she’d be back.

My head had been on a swivel for many years by the time I got to the Sinai, and I had learned many lessons on how to function in different environments. To sleep, we would place cotton gauze in our ears and nose then cover our mouths with a surgical mask. This was a nice little trick and it worked to keep the biting flies from entering our noses, mouths, or ears but it did not keep them from drinking. It was a small victory but a victory of a psychological sense is just as worthy of praise like any other. On this morning I removed the sweat soaked cotton gauze from my ears and nose and untied the surgical mask that covered my mouth. Then I scraped the bodies of flies that had gotten under the mask and had passed from this life to another sometime during the night. There would be plenty of time later to change the sweat soaked socks of the evening for drier and more comfy ones. We would tie the wet socks on our ammunition pouches to dry during the day. This was all just part of being in this barren hot and dry wasteland.

One can only experience, tolerate, and berate the environment when it’s 125 so early in the morning. With the heat, the ever present flies, and the spiders that you know are creeping along your arms and legs when sleeping, it becomes easy to get distracted and stressed. Gotta laugh because if you start crying you may never be able to stop. The Godsend was that the patrol was only ten days long and then you got to take a shower and sit on a real shitter. And we had only three days to go. But still, this environment and the job that needed to be done all worked like a system of gears and pulleys as it pulled, cranked, screeched, and devoured one’s energy and will.

Chow was done and our team of five was awaiting the helicopter that would bring us fresh water and more food. Chow or grub, who knows where these pet names for food came from, consisted of three year old MREs (meals, ready to eat), which were the latest in Army rations. Guaranteed to last forever, and I can attest to that fact, they were usually the focal point of morning bitching and griping by anyone and everyone. They were always FUBAR, a military acronym that stands for “fucked up beyond all reason”, and served only to fill an empty belly. We were also waiting for new batteries for our radio, the only link back to our fire base and the command center. We had three days to go on this patrol and had only several kilometers to cover during the remaining time so we were sitting sweet. We was cruisin’ on the downhill slope, we was next to go home to the showers!!!! And we were all ready to call the States when we got back to the fire base. We were happy little campers. I should have known.

No one person heard it first, that dull thud, but we all saw the brown dust in the dawn light of early morning. Screams. Pitiful, high-pitched and frightening screams came from the cloud of brown dust less than twenty-five meters away. Specialist Billy McCarthy, while returning from relieving himself, had found a land mine and now portions of his twenty-three-year old body were lying about coloring the dawn brown sand with splashes of red.

I got there first as the team medic placed a tourniquet on his left leg below his crotch and fired him up with two quarter grain amps of morphine. The pulsating flow of red blood ceased as it turned into a trickle. The blood curdling screams turned into whimpers after a third hit of morphine. The minutes that passed seemed to drag on endlessly. He knew he was dying. We all knew he dying.

“Sarge, can you do me a small favor?” said Billy, blood oozing from his mouth, his face blackened from the explosion and smoke coming from his uniform.

“Hooah,” says I. “Whatever you ask.”

“Sarge, can you say the Gettysburg Address for me? Come on man, it should be a walk in the park for a guy like you.”

Like thunder exploding and resounding throughout the Grand Canyon, his death rattle, that gurgling, drowning sound that you hear about in movies, escaped. I don’t know why he asked me to do that, maybe it was the morphine.

I often look forward to the girl with red hair visiting me again. The truth is that I would trade what does show up in my dreams sometimes for any girl. Feather or not. In my dreams now instead I’m given a chance to relive that morning, that day, with Billy and the team. And again I hear that dull thud and see brown sand settling. And again I fail. And again he dies. And again I don’t know a fucking thing about the Gettysburg Address. And again I feel feelings of such intense inadequacy and guilt that I pray to never sleep again, or to sleep forever, maybe in place of Billy.

There is a prayer that is prayed by all who have failed at a personal or significant task. The prayer is for another chance. But time travels in only one direction. Time does not offer absolution nor does it provide consideration for extenuating circumstances. The awful reality is that there is no chance to redo anything once it is done. For whatever good it does me, I now know the Gettysburg Address by heart. I swear at times I think I’ve awakened in the middle of the night mumbling it aloud. I won’t read it and I won’t even talk about it. I know that if I really want to hear or feel it I can just fall asleep.

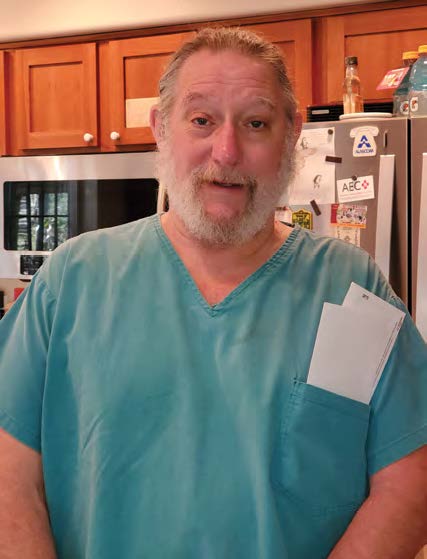

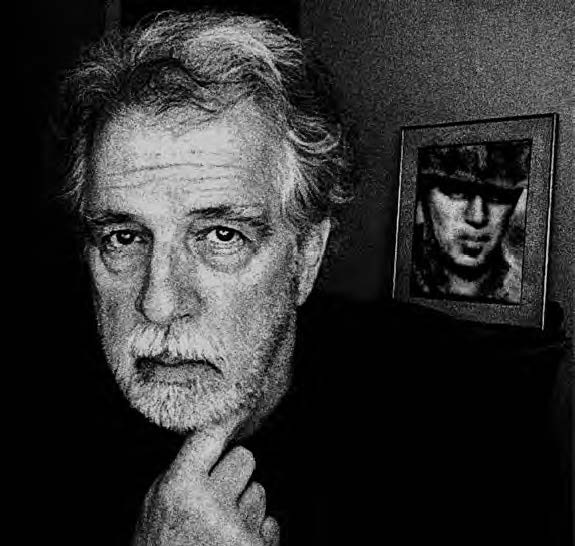

Stephen Allison grew up in a military home; his father was a career soldier and veteran of WWII. Steve joined the army in 1974, and after a career of over twenty years he retired, attending college at New Mexico State University and Eastern Washington University. Following graduation with a Master’s in Social Work, he served as a counselor at the Bellingham Vet Center for almost nineteen years, retiring in December of 2019.

Great Mistakes

by Jesse Atkins

Dead Reckoning (noun):

Jesse Atkins in 2002

The determination without aid of celestial observations of the position of a ship or aircraft from the record of the courses sailed or flown, the distance made, and the known estimated drift.

The act of dead reckoning is to dead reckon.

Fore, aft

Port, starboard

Head, bunk

Bulkhead, deck

Rack, p-way

Control, nav center

Plot, chart

Compass, divider

Shoal, reef

Dead reckon…

Days and hours play out like the penis drawn on the BPS-15. Cylinders of trash dotting the marks of fathoms. Day is night and night is day. Clock to Zulu, controlled, rigged for black. Life laid out in 30 minute dots, adjusted for drift, unaware of change.

Routine this, routine that. Clean, sleep, plot, shit, piss and do it all again. Only this time the BPS is a tree, the most ironic imagining you can imagine in the deep.

No green, no air, no sky, no dirt. Only salt, water, and grease; industrialized, sterile, void.

My history, my time, passes through space like the radiation through my bones.

Void, desolate, dead reckon…

Zenith, sightline

Red, right, returning

Duty, watch

M16, M9, 500

Sticks, ballast

Monotony

Dead reckon…

Division assembled

Charts arranged, changed, primed

Nav party called

Mooring lines a cast

Ship to sea

Claxon howls

Dive, dive, dive

Dead reckon…

Periscope, radar

Boredom, loneliness

Solitude, separation

Right hand

Left hand

New sock…

Time passes in the void seconds deeper than the last

Emptiness, foreign, new

Sea mist

Sunrise

Blue horizon

All aback, planes level

Steel beach

Dead reckon…

Pitch, roll, rise, plummet

Open, shut

Blow, discharge

Vent, head valve

Pop, whoosh, boom

Stale, controlled

Monitored

Family gram blank

Lullaby of whales

10 degrees port

Sins, mark-19

Plot, line, measure

Dead reckon…

Jesse Atkins served in the U.S. Navy on board the USS Alabama (SSBN 731) from 2002-2005 as an Electronics Technician Navigation 3rd Class. He is currently very active within the Veterans of Foreign Wars and has served the past five years as the Post Commander of William Matthews Post 1585. Jesse is a third generation veteran with his grandfathers serving in WWII and Korea, his father serving in Guam post Vietnam War, and his sister serving in South Korea and Iraq. He earned a Master of Education in Adult Education and a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics at Western Washington University.

I’m Not Broken

by Jesse Babcock

I’m not broken, I’m just struggling

I’m not broken, just nobody understands me

I’m not broken, I have just had different life experiences than everyone else.

I’m not broken, I am too strong to be broken

I’m not broken, I am a soldier, and soldiers cannot be broken.

I am a soldier, and I am broken, because we are made to be broken.

I am broken, because breaking me made me strong

I am broken, no matter how much I trained, nothing could prepare me for this

I am broken, and I have to understand why

I am struggling, not to be broken.

Spc Babcock Jesse D 671st En Co. Operation Iraqi Freedom March - October 2003. Fourteen Bridging operations. Multiple river patrol, convoy ops, foot patrol and tip of the spear support for the 3rd ID initial advance. Motto: “we probably won’t die.” Assigned weapon, M249 SAW. Vehicle BN: B114, “fat bastard.” Currently working for the Concrete public works department. If I had it all to do again, I’d bring more smokes and toilet paper.

22 a Day

by Andrew Englund

Browning killed himself. Blade Runner killed himself. Powell’s family won’t tell us what happened, but judging from what we learned about the circumstances in which he was found dead, he probably killed himself too. And those are just the ones I knew best. It’s bad, man. Almost every infantryman I know has already passed the point where suicide’s taken more friends than the Taliban. It doesn’t always come out of nowhere, but sometimes it does, and since I don’t fuck with Facebook, I’m usually one of the last to know.

‘Hey killer, have you heard from Ginge lately? His ol lady messaged Me. Nobody can find him for a couple days now. Copy?’

I called immediately. When it went straight to voicemail, I knew. He’d been prone to drinking benders in the past and I wanted to pretend it was that. But I knew.

Still, if I’d been anywhere within a thousand miles, I might’ve taken off that night to go look for him. Instead, I resigned to the facts and resorted to going home and staring blankly at the ceiling, praying. When my phone went off at 2:00 am, it broke my heart, and I just lay there for a while, preparing myself before reaching over to see what it said.

‘Ginge is down man. Don’t know what happened yet. Still waiting on word.’

I couldn’t accept it. He’d been one of my best friends. The best man at my first wedding. There really isn’t another way to interpret what I’d read, but fuck if I didn’t look for one. Hoping on hope, I asked Froggy to lay it out as plainly as possible.

‘What exactly do you know?’

‘His ol lady messaged me and told me he died.’

‘Jesus man’

‘Thanks for telling me’

‘No problem, brother. I was supposed to keep it on the DL until his family made the announcement but I feel like he would’ve wanted us to know.’

I didn’t cry, then. I didn’t do anything. According to my phone, I just sat there staring blankly at the closet, or whatever was in front of me, for the next six minutes.

‘Suicide. Shot to the chest. Left a note. Don’t know what it says yet.’

It was a beautiful funeral. Weapons Platoon showed up in force, plus a few of the other Kilo guys who’d been lucky enough to know him well. We all got to meet Klaus, the Green Beret that Ginge had idolized and told us so much about, and talk with his parents and uncles and sister and girlfriend and a lot of really great people who traded stories with us, confirming from different angles what we’d all come to learn about him over the years. In the chapel, the family’s pastor gave a heartfelt and comforting sermon to his mom and stepmom, and I guess the rest of us too, and his brothers and cousin had some really funny things to say about him. Apparently, Ginge had always been a terrible driver.

When the ceremony at the cemetery was concluded, after the words had been said and we’d done our best to choke out the Marine Corps Hymn, Kilo Company had a little assembly, and the bottles and flasks started coming out of everywhere. It was like being back at the barracks, except everyone had a suit, a beard, and some of us even had a career.

Among them: McLovin was getting looked at by the FBI. For recruitment, that is. Grizz had been the West Coast Director of a major cannabis corporation but broke off with them to start a business of his own. Bizzo was up in Montana working in a mine and raising kids, and Tom ran a business where he went around cleaning up crime scenes. His first day back from the funeral was a gunshot suicide. No bullshit. And fucking Voshell. That fucker was living in a van and bouncing between a bunch of different marinas to make a shit load of money doing underwater welding.

“Wow, man. That’s badass.”

“It’s alright. Nothing like throwing those rounds downrange though. But hey, you gotta give up on the wild life if you’re gonna have a real one. You know?”

I smiled.

“Logan never gave up. Last I heard, that motherfucker’s getting paid to jump out of planes.”

Things got quiet.

“Bro. Logan killed himself.”

Andrew Englund is a writer and nomad who currently lives in Flagstaff, Arizona. A veteran of the Marine Corps Infantry, he writes fiction and poetry about war and other veterans’ subjects. Englund is a father, a musician, and an MFA candidate at Northern Arizona University. He graduated from Western Washington University with a BA in creative writing.

American Djinn

by Keith Fletcher

One soldier shot the dog; another shot the wife. They’d just hit Karim’s compound. After the shooting, the soldiers scurried about gathering evidence, avoiding the dead wife on the floor, her head canoed and oozing red, an AK just out of reach of her pulseless palm. They ziptied the detainees and placed spray-painted goggles over their eyes. Scharff cut the fingers off the dead ones to run through biometrics later.

The soldiers stepped off the objective, detainees in tow. The valley shown viridian in the monochromatic green moonlight of the night vision goggles. They slithered up the mountain in a staggered line of green optoelectronic dots, into the darkness above. When they got to the top of the ridge, they established a security perimeter around the HLZ.

Scharff pulled out the ziplocked baggy of fingers. He had his interpreter, Atiq, run the digits over the biometrics device while he logged the entries.

Keith Fletcher, 2010

“This is bad juju, man,” Atiq said, sighing.

“It’s just a job.”

“Bro. It’s dead fingers, man. You get cursed for doing this kind of shit. The bad kind of curse, one that follows you to the grave man.”

“I thought you didn’t believe in that ‘superstitious shit’.”

They finished, placed the fingers back in the bag and packed up the biometrics system. Captain Bert walked up to them. “Birds down in five mikes. You still got them fingers?”

“Yes Sir.”

“Let me see them.” Scharff pulled them out. Bert grabbed them out of his hand and looked them over. “That’s some sick shit.” He had a big grin on his face. “Good work.”

“He’s a sick fuck, bro,” Atiq said, after Bert was out of earshot. The Captain was a real meat head, at five foot eight, with a swollen neck and arms that prohibited him from touching his back. As the sound of the approaching rotors echoed through the mountains, Scharff thought back to before the raid, when Bert had gathered the soldiers and launched into his pre-mission pep talk: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers…” He thought the Shakespeare gave him that warrior poet edge, but for the most part, it only reified the soldiers’ belief that he was a real class-A douchebag. Throughout the battalion, his name had taken on the verb form of the grosser bodily functions. For instance: a soldier retiring to their jack shack might say “I’m going to go rub out a Bert.” A soldier going take a shit might say “I’m going to go drop a Bert.” There was an arched 12-inch-penis over the plywood doorway of a pisser, with BERT carved across the shaft, etching his name into the annals of FOB history.

The helicopters touched down, the soldiers and detainees loaded up, and they lifted off. As they rose into the crisp mountain air, the dawn light slowly crept across the easterly peaks. Scharff peered out the window. The valley floors below were scattered with glacial till and ancient river rock over which flowed braided white capped streams. Across the valley, mountain peak after mountain peak thrust into the air like the exposed bone shards of a heap of amputated limbs, the torn flesh flopping down into jagged draws and ravines.

They touched down at the FOB, offloaded, and took the detainees to the DHA. “Get a couple hours of shut eye. We’ll start Karim’s interrogation at ten. We only have 48 hours with him, before the Task Force picks him up.”

“Sounds good man.” Atiq took off in the direction of his hooch.

Scharff made his way to the office. Jones was passed out over her keyboard. She woke when he shut the door. Scharff dropped his assault pack and removed his body armor and helmet. Jones was a SIGINT collector from Scharff’s unit. They’d established a mutual rapport over combining their intelligence to action targets. After a Reaper had dropped 500lb bomb on the first target they developed together, Jones had entered Scharff’s hooch and pushed him down into his bed. Now, they celebrated in such a manner each time they scratched a target off the JPEL list.

“How was it?” Jones asked.

“Good. We got him. You want to get some chow?”

“Sure.” They went to the chow hall and grabbed a table in the corner.

“You alright?” Scharff asked.

“Yeah. I’m just exhausted. I’m tired of this shit.”

“Yeah?”

“I either have to be a bitch or a slut, and I’m not a slut so I guess I’m just a stupid bitch.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Yeah, not to you. You don’t get it.”

“Get what?” Scharff leaned in as Jones drank her coffee.

“That dipshit in Ops was drooling all over me again, and I tore into his ass, and now everyone in Ops is pissed at me, like I’m a big, fat, snarling bitch and I’m sick and fucking tired of it.”

“You want to get out of here? I’m not even hungry. I just came for the coffee.”

“Fuck it. Yeah. Let’s go celebrate. I’m sorry—I’m just tired.”

They went back to the office and into the shura room. They lay on their backs on the wool Afghan rug. Jones rolled over on top of Scharff. Her thighs pressed down on top of his, locking him to the floor. He reached up to unzip her jacket and she slapped his hand off and punched him in the side of his face. “Hmph,” she almost laughed, when he winced. She unbuttoned his trousers.

When they were done, they went out and lit up a smoke, and sat on the stoop.

“Do you like it, what we do?” Scharff asked.

“Yeah. Of course. I’m just tired of the Army.”

“I think I’m addicted.”

“Addicted to what?”

“I know it’s fucked up, but what we do, tracking people, hunting them. I’m addicted. There’s no replacement and—like, I know that we’re up to our necks in a river of blood,” Scharff let out a stream of smoke, “—but I’ve found my purpose and it’s this and sometimes I want to suck start my M9 and other times I want to dance naked and howl at the empty moon. It’s all fucked up in here,” Scharff said, jabbing his head. He and Jones had friends who’d tried to find alternatives—heroin, bank heists, serial killing, etcetera, etc.—and most were in prison, or dead. The ones who pretended like the addiction wasn’t there, like it was some switch they could just shut off, they weren’t any better off: two-parts booze, one-part broken marriage, and sprinkle with suicide to flavor. There was no replacement.

“Jesus Christ, man. I’m checking you in to behavioral health when we get back stateside.”

“You and me both.” Past the wall of the base, they could see the tan, rammed earth walls and roofs of the neighboring village. Poplar and olive trees grew between the buildings. The sweet smell of wood smoke wafted over the base walls. Beyond the earthen village, green terraces worked their way up the valley wall. They finished their cigarettes in silence.

A couple of soldiers brought Karim into the interrogation booth. Atiq and Scharff were waiting for him. “Tsenge. Zama num Scharff de.”

Karim stared at Scharff and Atiq.

“I’m going to ask you questions about the insurgency. I don’t care who you are or what you’ve done. I’m not here to get a confession out of you,” Scharff said. Atiq translated. Scharff explained that he was Karim’s advocate, that he was there to defend him and in order for him to do that well, he needed to get to know him. They discussed Karim’s childhood on a small pistachio farm outside the provincial capital, his wives, Muska and Reshmina, and his children. They discussed the woes that faced Karim’s people. Karim was the provincial insurgent commander and Scharff had been developing his target packet for months. Karim was a family man and a folk hero, a real robin hood of the Hindu Kush sonofabitch, so Scharff had decided on a love of family/pride-and-ego-down interrogation approach. “Tell me about the insurgency, Karim. That’s something I can take to my boss. Help me prove that you want to cooperate. Meet me halfway. Do it for your people. Do it for your tribe. Do it for your family.” They’d been at it for hours.

“Where is my family? Where are my children? Where are my wives? Why won’t you tell me how they are?” Atiq glanced at Scharff.

Scharff pulled out a piece of paper from his folder and slid it face down across the table. Keeping his hand over the top and looking into Karim’s eyes, he said: “It isn’t pretty. I’m sorry.”

Karim turned over the piece of paper. He shuddered. It was Reshmina’s dead body, head hollowed out, lying on the floor of his house from the raid the night before. He grabbed a handful of his hair with each hand.

“This is your fault, Karim. Help me stop this from happening again.” Scharff grabbed the photo, then he and Atiq left the room.

“Damn, bro,” Atiq said. “That was heavy.”

Scharff lit a cigarette. The guard came in. “Well?”

“We’re done for now. Take him outside the wall for the night and put him on his knees in front of a battle position, so they can keep an eye on him. Strip him down to his underwear. I want to leave him out there overnight—let his thoughts ferment.”

Scharff turned in and fell into a deep, dreamful slumber. He was standing over the silhouette of a man sleeping in bed. The sheets were blue. He was envious of this man and his blue Egyptian threads and his down pillows. Towering over the body, Scharff slid his hand down and clasped his neck, gently first, then firmer and the sleeping man’s body jerked alive. The cartilage, tendon, and muscle squirmed under Scharff’s grip. Scharff started to slug away at the man’s face with his off hand, angry that he still couldn’t identify his victim. The sleeper started spitting and spraying blood and phlegm through his thin blue lips, into Scharff’s face. Then the sleeper relaxed, and his mouth opened gently, exposing his neat white teeth. Scharff looked closer and realized the sleeper’s face was his face.

THWAP!

Rat-at-at-at-at-at!

THWAP! THWAP!

THWAP!

Scharff jolted awake, threw on his body armor, and grabbed his rifle. The plywood door to his hooch was splintered across the floor and dark smoke shrouded the air. A 6-by-6 timber was on fire on the stoop. The battle positions were talking their guns back and forth, call and response, like Beethoven’s Fifth, the antiphony of war—

D-DU-DU-DU-DUH

rat-at-at-at-at-at-tat

DU-DU-DU-DU-DUH

rat-at-at-at-at-at-tat

—it wasn’t right. They never got hit with small arms. It was the occasional stray rocket or mortar or recoilless rifle—never small arms. The 155 Howitzers were silent. Smoking sandbags were shredded, were littered everywhere, as if they’d been dropped from the sky like confetti. Scharff stepped over the burning timber. A soldier ran past: “The gun line’s down! They hit the AHA! Red Bayonet! Red Bayonet.” Scharff bolted through the alleyway outside his hooch, towards Jones’ sleeping quarters. He rounded the corner. A group of insurgents were pouring through a smoldering hole in the base wall. Karim stood in the midst of them, barking orders. Bert and a platoon of soldiers rounded the adjacent corner: “Once more, into the breach!” They had fixed their bayonets. The insurgents opened on them with a volley of RPG and PKM fire. The soldiers closed the distance and started to stab and shoot their way towards the hole in the wall. Scharff was too dumbfounded to look away.

“Hey.” It was Jones. A bullet blew fragments of her cranium across the stucco wall next to Scharff. Scharff dropped to his knees next to her. He rubbed his hands across her body as if the friction might revive her. He dropped his armor and unclipped his helmet. He ran his fingers through her hair. Behind her, an insurgent with an SVEST ran into the TOC: Allahu Akbar! Dust and blood and bone fragments ripped out the doorway. He stripped off his clothes and rubbed her blood over his body. Across the way, Karim was slicing into Bert’s fat neck with a dull blade. A soldier next to Bert screamed Fuck You! as an insurgent stabbed into him with a bayonet.

Scharff reached up and held his head between his palms. He could smell Jone’s blood and taste her iron on his lips. It was still warm. He slid his hands over his lids and massaged his fingers over the pink fleshy part where the nose meets the eye. He gouged his fingers into each socket and clawed out his eyeballs.

A hand gripped his shoulder. “Bro—we’ve got to get out of here.” Atiq helped him stand. They walked towards the insurgents, Scharff naked and eyeless. The insurgents lowered their weapons. Atiq and Scharff walked through the hole in the wall.

Four men sat huddled, talking in a hushed tone near a fire pit. “He’s part lizard, part human. He dips his tail in village water and the children turn to stone,” one said. “No, you stupid donkey fucker. He’s a British soldier trying to find his way back to Kashmir,” said another. “Neishta,” said the third. “He’s a German Nazi looking for the source of the sun in the eastern slopes.” “You’re all wrong,” said the fourth man. “I’ve heard his howl. He’s a djinn looking for his eyeballs.”

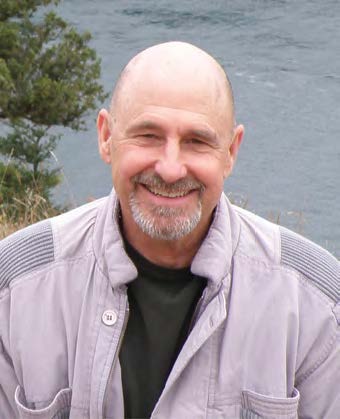

Keith Fletcher did three combat tours in Afghanistan where he served as an intelligence collector and fell in love with writing. He lives in rural eastern Washington, where he teaches Middle and High School English. He graduated from Western with a BA in Secondary Education.

Iraqi ICU

by Lynne Graham

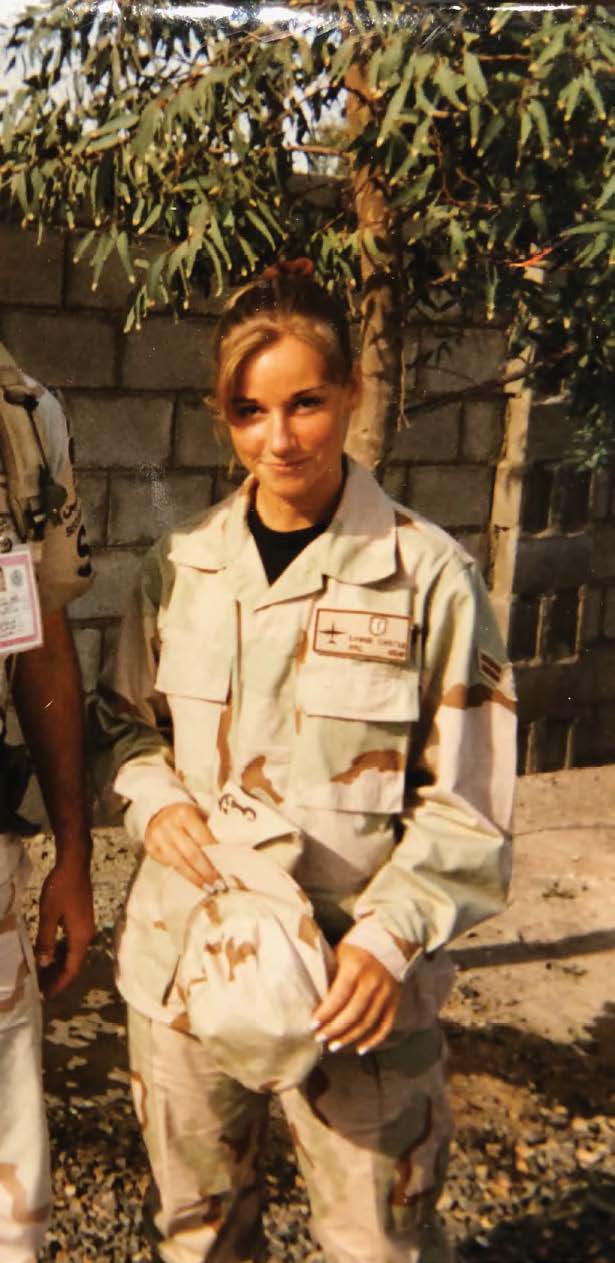

Lynne Graham in Saudi Arabia, 1992

I am quick to volunteer. I am desperate to find a way to feel more productive. That’s how I end up standing in the Iraqi ICU ward while deployed. It is merely a tent with hospital beds lining each side of it and people rushing around. Every bed is occupied but the patients in each one appear a little different. I had volunteered to help the staff, but with no real medical experience, I could only do a few things. So, I help bathe patients and change the bandages on their wounds. At the first bed, I can’t shake the need to hold the hand of its occupant. They, the staff, tell me that’s she’s five years old, but she’s so tiny that she barely looks to be two years old. She’s unconscious but I hold her hand anyway and intently watch the machine that’s helping her to breathe. There is a man in the next bed who appears to be in much better condition. They tell me he’s her father. Immediately, they answer the question they know I’m thinking. “He used her as a shield during an attack,” they say and continue with their work. I sit there stoking her small hand for a few more minutes before I can continue with my task of bathing her frail body. Lost in sadness as I work to complete my task, I suddenly realize I’m being called to a different bed. I look up and a woman with an Australian accent is asking me for help. I quickly move to the bed where she is standing. Before I can even focus on what is happening, I am holding the man in the bed’s intestines in my hands so they can clean the area around the massive wound in his stomach. I know from my basic first aid class that the organs cannot be put back inside of him in this environment. Instead, I help to hold his intestines securely on the cleaned area and a bandage is placed over the entire stomach to keep it from infection until he can be moved and treated properly. Just then, I hear a groaning sound from the bed behind me. I bring water over to the man who made the sound. He grabs my hand in what feels like desperation. He speaks very quickly in a language I don’t understand. He doesn’t appear to be in pain, but he seems desperate to tell me something. I try explaining that I don’t understand. A staff member comes over and explains to me that UN forces haven’t been able to find an interpreter that speaks his dialect. So, no one knows exactly what he needs. My heart breaks that he is unable to communicate with anyone. He must feel so lonely and scared. I notice a bed at the other end of the room. There is a sheet drawn around it for privacy. They anticipate my question and patiently explain that he is an Iraqi General. They continue by explaining who is in the bed next to the sheeted one and tell me that he is the bomber that caused the chaos that brought all the patients here. His bed is exposed unlike the General’s, but his eyes are covered with a blindfold. I’m not sure what to think about all of this. All I can do is watch the staff in awe as the continue their work. I try to stay out of the way and help in any way I can. The time goes by quickly, and before I know it, my first volunteer shift is over. I know I will volunteer to come back.

Lynne Graham served in the United States Air Force for 20 years with over 1500 days deployed overseas in support of multiple combat campaigns. After retiring from active duty, she returned to Washington with her partner and young daughter to be closer to family. She recently received her Master’s in Social Work from the University of Washington and is currently a counselor for the local Vet Center.

Writing Resources for Veterans

“If we fetishize trauma as incommunicable then survivors are trapped — unable to feel truly known by their nonmilitary friends and family…. It’s a powerful moment when you discover a vocabulary exists for something you’d thought incommunicably unique.” —Phil Klay, author of Redeployment, winner of the National Book Award

Writing Resources for Veterans

- Veterans Writing Project

- 0-Dark-30, the Literary Journal of the Veterans Writing Project

- The Red Badge Project, Seattle

- War, Literature, and the Arts Journal

- The Warrior Writers Project

- The United States Veterans’ Artists Alliance

- The Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans, The Iowa Review

- The Deadly Writers Patrol, literary journal

- The Line: Veterans Literary Review

Why It is Important for Veterans to Give Voice to their Experiences

- Because their stories provide the historical record of our times. American literature has a long and distinguished tradition of writers rendering the wartime experience.

- Because Americans ought to have some understanding of what it means to serve their country.

- Because hearing veterans’ stories helps to close the gap between Main Street and the military.

- Because it eases the transition of veterans into the community.

- Because those who served deserve to be welcomed home.

- Because we need to make informed decisions about foreign policy in the future.

- Because a writing practice may become a lasting form of self-care that improves emotional and physical health.

Haircut

by Russ Kapp

Following my high school graduation with the senior class of 1965, I enrolled for the fall semester at the Kansas State Teachers College of Pittsburg. I was looking for a smaller and less expensive college to begin my freshman year rather than diving into a more intimidating university setting with larger classes and campus terrain. I arrived prepared to enter the school of liberal arts virtually clueless as to the difference between degree program requirements and the additional requirements necessary to successfully graduate from a land-grant state school. The distinguishing factor that was soon to burst my euphoric bubble of college freshman bliss pivoted on the fact that this type of school’s federal funding mandated that all males take a two-year course in military science in order to successfully graduate. Rack this up to sticker shock or carelessly skipping through a land-grant minefield, since my initial strategy was to somehow avoid the draft after high school. In short, this amounted to a clandestine version of the military draft commonly referred to as the US Army’s ROTC college program.

As is often said, the devil is in the fine print. I ask you, how many small-town, soon-to-be college freshmen, fully topped-off with piss and vinegar, are likely to bother reading such micro-font size material, much less, deeply comprehending the meaning of it? Another often quoted nugget of wisdom, which readily applied to my military draft aversion simply goes, “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.” I had been cornered, and I was fresh out of options by that point. Thus, I turned in my registration (more accurately, resignation) and came out from my mental barricade with both hands held up high, waving my white flag. It would be safe to say that I did not come down from the higher education mountain laughing at any point during my freshman year.

Call me simply spoiled or wise, but I called it quits after the spring semester ended. And onward I went to a plan B during the following summer of 1966, exploring and mulling over alternatives to being halfway across the world and a holiday platter turkey by Thanksgiving Day courtesy of a surprise direct-hit mortar attack. Later, as the fall season fast approached, the dreaded clouds of war and blinding dust parted long enough for the descending angels of yore to announce a divine compromise in my fight with this fire-breathing draft dragon. I heard them singing, “For unto you this day, a U.S. Navy recruiter is awaiting your call in the little town of Kansas City. You will find him wrapped in a dress uniform and arriving at your home’s front door.” I henceforth, wasted no time in getting shipshape my plan of action. For the record, military recruiters are the epitome of driven salespersons since they are propelled by the intangible, a quota, instead of the easier sale of material items and money. Meeting the qualifications must be exhaustively rigorous.

Being of sharp mind and an impeccable dresser with a sterling silver tongue is just the beginning. Having a quick wit, anticipating questions with nearly instantaneous mind-reading solutions, and possessing the reassurance of a high school guidance counselor who can visualize glamorous future success stories are nearly guaranteed shoo-ins for the ideal military recruiter. After submitting to a regimen of induction testing and screening, I was provisionally selected for a six-year nuclear power technician “career” and designated program. I was immediately zapped into a sleep-walking trance, totally oblivious to another nugget of wisdom: “If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.” Sparing the details of what might have been construed as a bait-and-switch operation, I was suddenly presented with being disqualified from the “Nuke” program due to having corrected vision. Say what? Nevertheless, with no time to reconsider options (I was on my way to boot camp shortly), I gave my body and mind over to a different six-year enlistment program: Electronics Intel and Communications Technician. So be it. With boot camp and several months of introductory electronics schooling under my brass-buckled belt, I arrived at the Bay Area’s Naval Electronics Training Center on Treasure Island during the summer of 1967.

As luck would have it and totally unbeknownst to me, this was also the epicenter of the hippies’ Summer of Love with its central headquarters located in the San Francisco Haight-Ashbury District. Having been informed of this happening by a fellow classmate, my eventual first weekend foray offbase was to check out this curious hippie scene. I stepped off the city bus with an astonished look on my face, no doubt. Was I still on planet Earth? I had never witnessed the likes of a massive gathering of freaky young adults and kids. We were encouraged by our naval superiors on base to wear “civies” while on liberty downtown. However, as I surveyed the current scene there at the junction of Haight and Ashbury, I realized I was, in fact, still wearing a uniform of sorts. I was the only one among the throng of beautiful people with a close haircut, a close shave and sporting a pair of men’s slacks and a dress shirt. I was clearly outnumbered, and among the throng of hippies I was, in effect, the only genuinely authentic freak. Nevertheless, this scene became somewhat of a regular weekend destination. Somehow, I knew at the core of my being that I had finally found my tribe and the promised land. It would seem I was becoming a multiple personality disorder case; Clark Kent by day and Superman by night, a sailor in training weekdays and a counterculture warrior on weekends. During my entire stint of classroom training, I was never interrogated as to my whereabouts while on liberty off base. And yet, being aware that my designated military occupation required a full-blown background investigation to obtain the necessary top secret crypto security clearance, I was careful not to participate in any illegal activities while I was out and about. Who knew? Was I being subjected to an undercover watch, basically being shamelessly stalked? Whether that was possible or was merely an over-inflated sense of self-importance, my efforts at staying clean was the best policy given the next level of weekend off-base tribal participation I eventually pursued.

The weekend that became a major game-changer during my training stint began in failure. The one time I crossed the line attempting to gain entrance into a pole-dancing bar in California as a minor gave the door bouncers an opportunity to relieve their boredom by flexing some muscle groups. While attempting to fully embrace my disappointment and move on to a potentially bleak weekend, I happened upon on old-style indoor movie theater that had the words, “Avalon Ballroom” on the majestic overhead marquee. I politely asked the ticket booth hippie gal what was currently showing, and she quickly replied in one short breath, “Three bands, three dollars,” with a seemingly take-it-or-leave-it attitude. Clueless as to what I was about to discover, I replied, “Alright by me— here goes.” Once again, I was confronted with my off-base uniform, close haircut, close shave and proper attire, this time in the presence of a New Age audience seated on a bare floor where cinema seating had been previously. A lighthearted festive “vibe” permeated this live music venue with its moving psychedelic light show as a backdrop. I seated myself in a makeshift row close to the stage where a rock band was playing a top-40 song I recognized. As a large woven basket of fresh fruit was passing around and a smoldering joint followed as a chaser, I leaned over to a hippie chick seated next to me and shouted over the din of the loud music, “Dang! Those guys sound just like the Youngbloods.” She turned her pretty face my way and with a look of utter incredulity flatly stated those guys were the Youngbloods! And from then on, the Avalon Ballroom and its cousin, the Winterland Auditorium became weekend alternative duty stations while I was in training to become military spy support.

Russ Capp is a front yard Baby Boomer, a product of the heartland from a preacher’s family with a born affinity for dark comedy. He enlisted in the U. S. Navy and served six years of active duty during the Cold War aboard a secret surveillance vessel and on the coast of Vietnam aboard vintage diesel-electric submarines as an electronics technician.

Trigger Warning

by Malcolm Kenyon

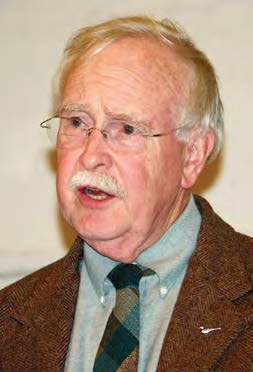

Malcom Kenyon in 1965

And here’s the question: what advice would I give to potential future veterans? Be very careful about what you think that you believe, and make sure that you really know why you believe it. Don’t accept other people’s beliefs without independent confirmation. Study epistemology: know where your so-called information really comes from. Refuse to be used: that’s your right, so fight on your own behalf.

Let others do their own dirty work: you owe this to yourself. Or better, mess with them— the war-mongers who advocate slaughtering millions of common-clay, like you are, to feed their ravenous factories, their bank accounts, to buy themselves Teslas to tailgate you with, to provide the rich and powerful with whores and members-only golf courses.

War is how “The Owners” divert this country’s attention from what really needs doing for the common good throughout the world, to what’s personally most-profitable to themselves, disguised in the name of Allah, Yahweh, or Jesus— that guy most-frequently voted for the past two millennia as the religious figure most-left-out-of Christianity— like, didn’t he purportedly say in Matthew 5:9, “Blessed be the peacemakers for they shall be called the children of God?”

Glory is a na ve chimerical illusion for mere mortals— a tragic self-deceit, a conceited self-aggrandizing lie— “glory” is the work of gods alone— the rest is sham, smoke-and-mirrors, and manipulation by the rich and powerful in their own economic self-interests.

The USA needs to revisit the issue of “national service”— should it be compulsory or voluntary? Why? Why should we ever have a draft? What should be the rewards for serving? Should the right-tovote be made contingent on an interval of mandatory public service? For two years maybe, like many European nations require of their citizens? Service is proof of an individual’s personal investment in the common good. Should this be only war service, or also peace service? It seems to me that there’s room for both. No one should be required to kill another human being against his/her will. If voting and other privileges of active citizenship are not ultimately made contingent on national service (which requires a constitutional amendment, of course) of necessity it’s already readily-apparent that cowards, shirkers, and the mentally-defective (viz Donald Trump and his family) will totally dominate U.S. politics— just see how it is now!

Corporations are not people, and the Founders could not have possibly anticipated that absurd assertion. Corporations emphatically do not have the same rights as individual humans— legal arguments to the contrary are self-serving hogwash and sophistry. Only “vested citizens” should be eligible for public office. There should in every case be term-limitations in the interest that the maximum number of citizens are able to hold some office-of-trust during their lifetimes. Consider Iceland, a direct democracy in which one out of every two citizens holds an office of some sort in their lifetimes— fifty percent— they also have the oldest constitution on the planet, by the way— almost a thousand years old.

So what has become of the Peace Corps? VISTA? Americorps? Do these entities still even exist? Who goes into these agencies and where are they sent? What are the rewards and incentives? Do we perhaps have need of a GI Bill for our peace-workers as well? Is peace somehow less-important than killing people? We veterans do not have a separate fate from that of the rest of our nation: our destiny is bound-up in the ultimate fate of all of us, just like everybody else— we are not an exception! The trick is to bend our nation to the service of the many and not to the few— this is a classic unsolved dilemma of all human society down through recorded time.

History’s lesson seems to be that, in the interest of “power to the people,” SMALL is definitely better— great size and great power only favor the rich and the ruthless in matters of war and economic domination. Count one-by-one the geographic sizes and populations of the world’s nations, versus their system of governance— do you get the picture? Is there a detectable, consistent socio-political rule at play here?

Perhaps this issue/conundrum is unsolvable, and ultimate justice will be administered by the blundering strike of some clueless wayward asteroid. Or, if you prefer, some pompous anthropomorphous know-it-all deity with a likewise anthropomorphous winged-retinue will descend In Glory from the ceiling of life’s theater at the end of Act-Three to set things right, like Euripides always had to end things because he made such a bloody mess of his plots.

But by-and-large, things will never be set right in the finite lives of nameless billions. Is our fate like that of mayflies? And what vanity makes us feel that we’re somehow better than insects, save that we’ve written our lies into our theology? “What is man that thou art mindful of him?” the Psalmist tells us, with perhaps more honesty (Psalm 8:4). The answer to that rhetorical question is theological and not political, and perhaps we’d best not pick sides?

As individuals, what exactly were our personal motives to go to war? Adventure? Glory? Escape from boredom, or our families, or seemingly-impossible economic circumstances? Escape from an insurmountable socio-economic log-jam? From out of perceived patriotic duty? Fear of the draft? Orders? Sadistic personal impulses, a thirst for glorious homicide and pillage? An opportunity to bully others, especially our perceived racial inferiors— with impunity? I’ve seen all of these things.

“He who taketh up the sword shall perish by the sword,” Jesus is said to have observed (Matthew 26:52). But on what scale or timetable? Those of us who are still alive and writing about this subject, obviously apparently escaped that particular fate. Or was this said mainly to predict the long-term fates of nations? Are we not all ultimately protein in a chain-succession of future predators much like ourselves? Or will we ultimately be consumed in flames? Heaped on a hecatomb of human sacrifice— the living flesh of our great democracy piled high to honor our proprietary self-intoxicated bloody-minded anthropomorphic gods— incinerated as it were on an altar of our own making? But that’s not the entire quotation— the first part is often left out. Jesus is said to have said first, “Put up thy sword into his place”— in other words, “put that damned thing away before you cut somebody with it.”

Can I say all this? Or is religion taboo, unless of course you’re an evangelical? Is this a fair fight, or are my enemies entitled to hold my arms behind my back while their henchmen punch-me-out? Religion and a blind-belief in the invisible is at the philosophical roots of our American political intransigence— we seem to learn our intransigence in church. Who dares to argue with fanatics? The Shiites and the Sunnis are beating each other’s brains out over fewer differences than exist between Baptists and Presbyterians. Hindus persecute Muslims in India. In Myanmar, Buddhists persecute Muslims. The Chinese Communists persecute all non-indigenous religions. The Muslims have historically persecuted the Baha’is and the Zoroastrians. The only true god of mankind appears to be Mars.

Our national fertility-rate has dropped below the replacement level. I can easily see this when I count the children of my friends who are still in their thirties and forties— most of them are childless. Where then are we going to get our warriors? Particularly if we pursue our anti-immigrant proclivities? From among those of our population who are willing-enough to call themselves “militia” and run around in public with AR-15s dangling around their necks, stirring-up trouble with people who progressives keep insisting on calling “people of color”? These self-appointed “militias” somehow don’t look to me to be good potential troops, unless soldiers no longer need to be able to read or shave or count past ten.

I’m not under any delusion that the USA is a “democracy” in any way, nor even a “representative republic,” given gerrymandering by both political parties. Therefore, I’m not really concerned with changing national policies— I, and probably you, have no meaningful control over that, nor even input. I’m only specifically addressing the matter of potential soldiers here. If you’re a potential soldier, I say to you: don’t go! Look at those among us who have come back from Korea, Nam, the Gulf War, Iraq, Afghanistan— talk to us, ask us. Shut up and listen to our answers. Don’t let yourself be used— don’t go. Let the Trump family get out of their condos and their Teslas and go down to the recruiters— those who benefit should pay the check.

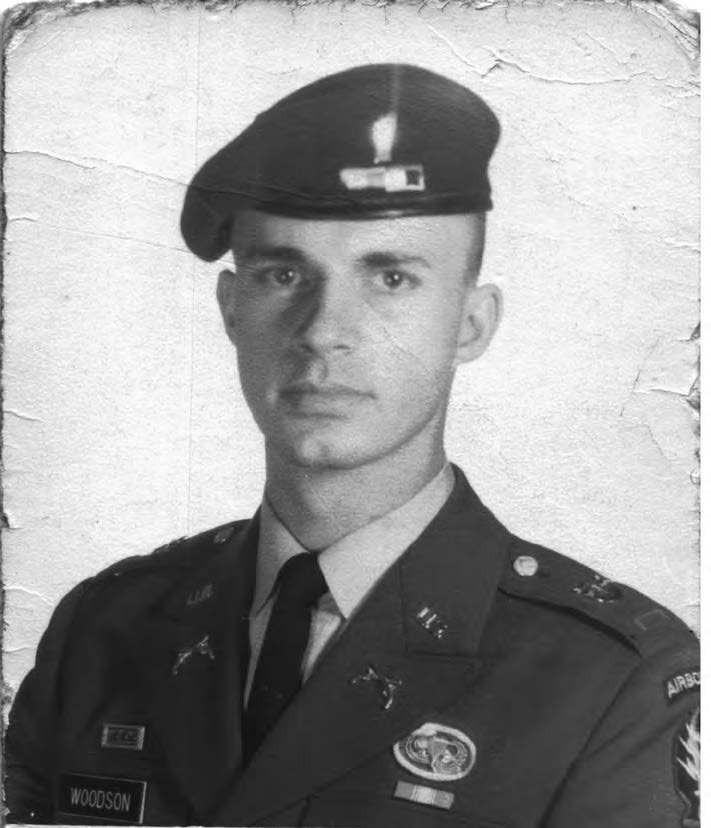

Malcolm Kenyon served as a commissioned officer in the United States Navy and fought in Vietnam, where he was Chief Engineer of a 2250-ton destroyer. He has since been a marine mechanical technician, technical writer, machinist, toolmaker, structural weldor, assistant professor of technology and an ESL teacher. His writing has appeared in Noisy Water: Poetry from Whatcom County; Poetry Walk: the Second Five Years; and Padilla Bay Poets Anthology, among others.

The Long and Winding Road

by Michael Novotny

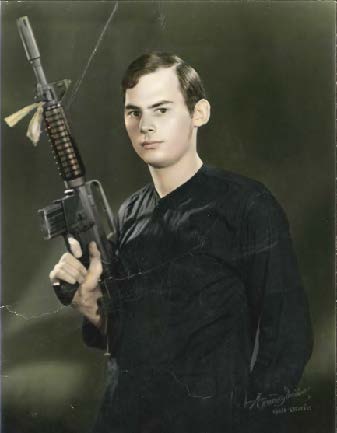

Michael J. Novotny, 1968

The 1st Cavalry Division had arrived in I Corps in time to play a major part in defeating the Tet Offensive in 1968. That is when I joined my unit. After that task, it chased after the remnants of North Vietnamese units in pockets of resistance. Some of those pockets, well, resisted. I was used as an occasional aerial observer. I was assigned to Headquarters Company of the 2nd Battalion 19th Artillery, a direct support unit with three batteries of 105mm artillery. I was still recovering from knee surgeries at Fort Bragg and couldn’t be used as a forward observer, the typical initial assignment for new lieutenants, so Second Lieutenant Mike Novotny was doing odd jobs. I was the ammo officer. The batteries called in their needs and we broke down pallets of ammunition and put them in cargo nets and when the “Hooks”, CH-47 Chinook Helicopters, came in to sling them out we hooked them up. The ammo section hadn’t had an officer for quite a while, and the staff sergeant running it had been doing a fine job without one. The ammo section left LZ Sharon every day and went to the ammo dump at Quang Tri to prepare the loads. I stayed at LZ Sharon and took the orders and told them what they could or couldn’t have. What they could have depended on what was available and what helicopters were available to haul it. Sometimes they just wanted the ammo in the cardboard tubes it came in. Other times they wanted it in the wooden boxes that contained two rounds each. They would use the boxes filled with dirt to build bunkers. You could fit less rounds when you sent it in boxes.

Another job I had was Property Book Officer. Every battalion has a property book officer, a senior warrant officer that did the technical job of keeping track of equipment, ordering more, and writing off things that had been damaged or sometimes lost. Our Property Book Officer was killed or wounded during a rocket attack, it was never clear to me which, just that he was gone, and we wouldn’t get a new one for a while. There were cabinets of forms and records that seemed to be a cross between fairly logical and foreign language. I had no training at all in these tasks. I saw a senior warrant at our little club drinking apart from all the pilot types. He was drinking Johnnie Walker Red. The next day I took a jeep and went in with the ammo section. After things got organized, the Sergeant and I headed for the Base Exchange at Quang Tri. They didn’t want to sell anything to Army types. Somewhat disheartened, we drove past the MACV compound in Quang Tri City. They had a club, and a drink would lift our spirits. We stopped and found their little club. There were bullet holes all over the place, but they shared that they had withstood the Tet Offensive, in part because of the Cav and would only be too happy to sell us a couple drinks. While imbibing, the subject of purchasing came up and the bartender got the sergeant in charge of the club. He could spare some for a small markup, what did we need? A couple bottles of Johnnie Walker Red and three or four bottles of whiskey. He gave me Johnnie Walker Black, all that he carried and Old Granddad 100 proof. He asked me to keep it a secret. He couldn’t supply much. When I returned to LZ Sharon at the end of the duty day, I sought out the property book officer, who was assigned to 2/20th Aerial Rocket Artillery. I found him in his little wood floored tent; it looked just like my PBO tent, but better organized with no stacks of papers laying around. At first, the crusty warrant wasn’t very excited about helping, but when I produced the bottle of scotch, he was much more willing. It turns out he preferred Black Label, but the club couldn’t get it. He came over the next day and got to work. In two days, he got everything in order, gave me a stack of completed forms to sign and said that was all he could do this month, but he’d be back next month do it again.

West of us at the Khe Sahn Combat Base a regiment of Marines along with Army, Air Force, and ARVN units defended the base against a North Vietnamese force that included three infantry divisions and numerous supporting units. The road was cut, and all supply came through the air. The base regularly took over a thousand rounds of artillery a day. They sent thousands more back from their own artillery in the base.

A brigade of the Cav had defeated the regiment that was maintaining a supply line between Hue City and the A Shau Valley, long an enemy stronghold. Major General Tolson wanted to go into the A Shau and clean it out. But even two-star generals must follow orders, and he was ordered to develop a plan to open Highway 9 to Khe Sanh and break the siege of the beleaguered base. He did as he was ordered, and Operation Pegasus was born. It wasn’t all that clever of a plan. It called for Marine and ARVN units to drive towards Khe Sanh on the ground opening the road while the Cav air assaulted on both sides killing who they could and driving the rest away from the advancing troops. He would also start encircling the enemy units so he could whack them. He would establish temporary firebases to provide covering fires and he would chase any surviving North Vietnamese out of the area.

On the micro level, the 2/19th headquarters prepared to move west to Ca Lu along with the batteries of artillery. They would leave most of headquarters in place at LZ’s Sharon and Betty. They wouldn’t need me. What they needed were truck drivers. Most of the able-bodied enlisted men had gone out to the guns to replace losses. So, I volunteered to drive a truck. The supply sergeant wasn’t convinced.

“Well, Looo-ten-ant, maybe you could show me your Army driver’s license to drive a five-ton truck,” knowing most soldiers didn’t have Army driver’s licenses, especially officers.

Surprise, surprise. I had an Army driver’s license. In Armor AIT, I was licensed to drive a quarter ton truck, the venerable jeep, and the 60-ton main battle tank M48/ M60. I showed him my license. He was a bit taken back but was desperate for drivers so he handed it back to me and said, “Yes Sir, I guess if you can drive a tank, you can probably drive a truck.” He assigned me a vehicle and bright and early the next morning I fired it up and headed out to join the convoy. I had a load of timbers and steel planking and was in charge of the advance party for the battalion.

I would like to tell you how I cleverly maneuvered myself to the front of the convoy so I wouldn’t have to eat so much dust, but the truth is I just went where they told me to go. I was about fifth in line of a hundred or so trucks, just behind a couple gun trucks. While we were waiting to start out, a First Lieutenant, infantry type, with two grunts asked if they could ride along. Their unit was out there somewhere, and they had just gotten back from R & R and were looking to join them. I readily agreed since it is tough to fire a machinegun while driving a truck.

Around March 30th, 1968 and at the appointed hour, off we went headed east towards Quang Tri then north on Highway 1 to Dong Ha, finally west on Highway 9. We proceeded without incident through Cam Lo, the turnoff for Con Thien along the DMZ. As we approached the turnoff to Camp Carrol, two Blue Max gunships of the 2nd Battalion 20th Artillery (Arial Rocket Artillery) joined us. It was comfortable to have them overhead, but it was a reminder that if we weren’t in the danger zone before, we definitely were now. The gunships shadowed the convoy and we drove past the Rockpile. The next base would be Ca Lu, our destination. And after that was Khe Sanh.

We were only a couple miles past the Rockpile when I heard some loud pops from both sides of the road. Sounded just like mortars. We didn’t have to wait long for the rounds to impact. Yep, they were mortars, 82 mm it seemed like from the explosions. It seemed like maybe half a dozen tubes, all spread out. They poured their fire on the front of the convoy, probably hoping to stop us. Sitting targets are so much easier to hit. Hmm, I thought, maybe it would have been better to eat a little dust in the rear.

Since the correct thing to do is power through, naturally we stopped. The gunships peeled off to start taking out the mortars. I could see the tracers coming up to greet them. I was sure that help was on the way but knew that this was going to take a while, and the mortar rounds were coming hot and heavy right now. I could hear shrapnel rattling off my truck. I was not comfortable sitting there, and though the trucks in front of me were in the middle of the road the ditches along the side were not so deep and were dry. I engaged the front wheel drive, told the lieutenant to hang on, and pulled around the left side. The truck felt a little tippy but with ten wheels turning we managed to get around. At the front of the column was a jeep with a lieutenant colonel sitting in it bleeding from the neck. Steam was coming out of the hood, so I assumed his vehicle was disabled. The truck behind it seemed to have some damage too.

When I got back completely on the road, I high tailed it. I went maybe half a mile and stopped to take it out of low range. I glanced behind me, sure that I would see vehicles following me, but there weren’t any, at least not yet. Thinking back, I suppose I could have sat there while things sorted themselves out. After all who would engage a single truck when there was a nice juicy convoy available. But alas, I was a second lieutenant and that didn’t occur to me at the time, so I shifted into high range and took off for Ca Lu. I drove that truck about as fast as it would go.

It was pretty country, mountainous and covered with jungle so green on this sunny day. The road got worse and worse, but still never got too bad. We drove past a hundred spots that would have been ideal for an ambush. The lieutenant screamed at me to slow down but I was a former flat track motorcycle racer and was comfortable sliding a little, even if he wasn’t. I drove the hell out of that truck and it never faltered. Maybe two hours later we pulled off the road and into Ca Lu. We had not seen a living soul, friend or foe.

I stopped at the entrance and asked directions. My passengers took this opportunity to bid me fond farewell. They seemed a little shaky when they got off. I noticed that I was a little shaky too. All’s well that ends well. An engineer directed me to the designated spot for the battalion headquarters. I asked about getting some help with digging bunkers, and he assured me that the engineer commander would just tell a second lieutenant to get in line. When he was gone, I dug through my scant belongings. There were some extra clothes, lots of ammo for the machinegun, poncho liners, a cot, and two bottles of Old Granddad, 100 proof. Sadly, I put one in a backpack and went off in search of an engineer sergeant in charge of backhoes. I found him and a deal was struck. When the Chinook’s started arriving with the Conex containers that made up the Tactical Operations Center (TOC) there were nice deep holes to put them in. The timbers and steel planking would connect them and the whole thing would be buried deep enough to be rocket proof.

The Cav often flew two gunships over their major bases, the anti-mortar patrol. My first night there you could hear them circling at different altitudes with no lights on. No collisions that way. Shortly after dusk I heard the first mortar rounds drop. The gunship had fire on the tube before the first round landed. Other gunships joined them and fired on the position until there was nothing left but burned dirt. It was the last time we got mortared while I was there. After two days on April 1st, Operation Pegasus began. The Seabees and Army Engineers had focused on expanding the runway and it needed it. The Cav had over four hundred organic helicopters and they arrived en masse. One Marine wondered if everyone in the Cav had their own helicopter. I wasn’t needed at headquarters battery anymore, I so got to go observing more, but that is another story.

It seemed to me and the folks who outranked me that the enemy was withdrawing. There were lots of fortifications, trenches, etc., but not large troop concentrations. The troops we did find were not equipped to fight against the Skytroopers and were caught in the open a lot. The Division killed 1,259 against light casualties by the time Operation Pegasus was officially ended two weeks later on April 15, 1968. The Cav went back to their respective bases, mostly to Camp Evans, me to LZ Sharon. We prepared for our next adventure…the A Shau Valley was still waiting. It would not disappoint.

Michael Novotny served four tours in Viet Nam starting as an air observer in the First Air Cavalry Division and proceeding to advisor for Vietnamese Regional Forces and Popular Forces. Following an early promotion to Captain, Mike served as senior advisor to indigenous troops, Vietnamese and especially Montagnard (Hre and Rhade) primarily at Ha Tay CIDG Camp and Hoai An District. After leaving Vietnam, Mike taught irregular warfare at the career college before leaving the Army in 1971. He later returned to college graduating from Arizona State University with a BSW and New Mexico Highlands University with an MSW. Mike worked as a counselor and Acting Team Leader of the Phoenix Vet Center before moving to his current position as Bellingham Vet Center Director. Mike and his wife Pam have served as foster parents and do volunteer work in the area.

I Want to Make You Proud

by Thomas Renteria

My maternal grandfather was named Kenton Waymire. He and his brother Keith were raised on a small farm in Indiana by their grandfather. He served in the Airforce during WWII, the Korean War, and almost went to Vietnam while serving in the Reserves. He retired at the rank of Chief Master Sergeant, and now I know why he was always so particular about everything. In my experience, most senior leaders have the uncanny knack of finding the most microscopic of details in everything that they do. I remember him telling me as a child to make sure and use only two squares of toilet paper when going to the bathroom. He wasn’t joking and somehow always knew when I hadn’t followed his instructions.

He never talked about his time overseas and once told me that people who’ve seen real war typically won’t want to tell you about it. I’d read in newspaper clippings that his plane was shot down and that he had to parachute in behind enemy lines. This man was the epitome of everything that I wanted to be, and I loved him dearly. He had penned me a few letters when I was in Basic Training, and that was our last correspondence together—before he died just a few months later.

It was October 27th of 2007, and I remember the initial blast. It felt like someone took a Louisville Slugger and teed off on my forehead. That’s the last thing I remember before waking up and walking out of the vehicle on my own. Everything was bright and disoriented. I remember my eyes having a hard time adjusting to the light outside of the vehicle, but I stumbled out and up the stairs into the field hospital. I do partially remember being in the vehicle that day in Baghdad. Seeing weird lights and moving in and out of consciousness. Parts of it felt real and other parts felt like a dream. I had a flashback in Texas one time while driving, and it may have been the best glimpse of the day that I got blown up. I had been prescribed Ambien to help with sleep and had driven “unconsciously” to a nearby bowling alley in the middle of the night. Unfortunately, it took me totaling my car and two other vehicles for me to have that flashback. It felt very real. All I can remember is desperately trying to get out of the “kill zone.”

I left the U.S. Army in 2011, after what in total amounted to over fourteen-years of my adult life. Completely lost and wondering what the fuck was going on from one day to the next. Battling the voices in my head for control of an unexplained hypothetical conscious and subconscious environment. It literally felt like I was a zombie character on “The Walking Dead”. I wasn’t sure if I was coming or going at any given time.

In this weird state-of-mind.

Not feeling alive but knowing that I was.

Not exactly sure what I was supposed to do or where I was supposed to go.

For months after getting out, there was this emptiness inside of me, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. I was pretty sure of certain things about myself, but this was different and it just didn’t make sense. Once I started connecting with friends from the Military, it was obvious what was missing from my life. It was weird, when I was in the Army— I couldn’t wait to get the fuck out of there, and right after I left—I couldn’t handle being gone.

I read something the other day that stated: “Real change happens when a person is able to see through their own bullshit.” My post-traumatic stress created obsessive behaviors that manifested in the form of negative thoughts, severe substance-abuse, major depression, and crippling anxiety. I was existing in my own mental torture chamber and holding myself back from doing all of the positive things that I was capable of doing. Looking at the countless people that I’ve known in my life who have allowed mental anguish to control everything they do, and sadly disrupt other people’s lives in the process, I wonder. Such a selfish condition of the mind, and yet—can the person even see it? Do they even know what they’re doing? I can say, I absolutely did not.

Thoms Renteria (left) Kirkuk, Iraq, 2009